EPF PIN member Vicki Gray reflects on her time at Standing Rock.

When did it start? What does it all mean? How are we called to respond?

We’re talking, of course, about the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) that snakes 1,700 miles from the Bakken oil fields of North Dakota to southern Illinois and that, if completed, would transport 450,000 barrels of fracked, highly volatile Bakken crude through land sacred to the Standing Rock Sioux and under the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers.

The original planned route of the pipeline had it crossing the Missouri north of Bismarck. That route was scrapped in late 2014, due, according to the Bismarck Tribune, to the “potential threat to Bismarck’s water supply.” Shifted now to the south, through unceded land of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, it would cross the Missouri just north of the Cannonball River and the intake valves for the tribe’s water supply. This rerouting was done without an adequate environmental impact study and without any conversation with the tribe.

As construction neared U.S. Army Corps of Engineers land on the north side of Cantapeta Creek this April, the people of Standing Rock set up camp just south of the Route 1806 bridge and began efforts to block construction physically and through litigation. They obtained a stay in federal court and, over the summer, were joined in that camp – Oceti Sakowin or Seven Council Fires – by growing numbers of people from other Native American nations and allies.

Then, in late August, a federal judge lifted the stay and the Texas-based owners of the pipeline, Energy Transfer Partners, bolstered by new funding from Marathon Petroleum and Canada’s Enbridge Partners, began round-the-clock construction under the protection of local and state police, the National Guard, and company vigilantes.

The population of Oceti Sakowin Camp swelled to over 2,000 and, in September, clashes escalated between the Native American “water protectors” rallying round the cry “Mni Wiconi” (“Water is Life”) and “law enforcement” massively arrayed at the north end of the Cantapeta bridge.

“Law Enforcement” at the bridge

As protectors and journalists, exercising their First Amendment rights, found themselves facing armored cars, dogs, pepper spray, and rubber bullets…arrested, strip searched, and confined, in many cases, in dog kennels, the Episcopal Church stepped forward to stand with the people of Standing Rock. Bishop Michael Smith and the Diocese of North Dakota issued a strong statement of support. Presiding Bishop Michael Curry visited Cannon Ball and, describing what he experienced a “new Selma,” called upon Episcopalians to stand with their besieged Native American sisters and brothers. And, at its October convention, the Diocese of California passed a resolution applauding the Presiding Bishop’s actions; calling upon Bay Area Episcopalians to support the people of Standing Rock with money, study, and pilgrimage; and urging the Army Corps of Engineers to halt construction under the Missouri.

Still the construction continued – right up to the bank of the river – and violence threatened on an even larger scale. Then, in late October, the Rev. John Floberg, Canon Missioner to Standing Rock and Rector of St James Episcopal Church in Cannon Ball issued an urgent call for “more than a hundred” faith leaders to gather on November 3 at the bridge over Cantapeta Creek – an ugly frontline of burnt-out vehicles, a Jersey wall, and, now coils of barbed wire – in peaceful, prayerful, legal witness for justice and peace.

To his surprise, more than five hundred faith leaders – clergy and laity – responded…mostly Episcopalians, but Christians of all denominations, as well as Muslims, Jews, and others. Among that cloud of witnesses were a dozen or so – deacons, priests, laity, and a bishop - from the Diocese of California. Bishop Marc Andrus, Alan Gates of Epiphany, San Carlos, and a lay person or two slept in their tents in the camp. The older, less hearty among us slept in the comfortable beds of the nearby Prairie Knights Casino. All of us, however, spent considerable time in the camp, listening to the stories of those who had been there for months, imbibing their resolve, and rejoicing in the “opportunity to testify.”

For me it was a mountaintop experience…an experience that began with a November 1 evening arrival at Bismarck airport with two other deacons – Kathleen Van Sickle and Nancy Pennekamp (later joined by Phyllis Manoogian who flew up from Guatemala). Driving south on 1806, we were turned back at a National Guard roadblock and directed twenty miles north to a dirt road and a roundabout alternative route to Cannon Ball where we arrived close to midnight.

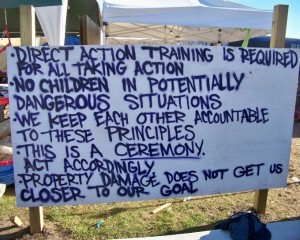

After lunch with most of the DioCal delegation, we headed to the camp, greeted at the entrance by signs insisting “No drugs, alcohol, or firearms,” directing new campers to obligatory non-violent direct action training, and, facing the highway, a banner, probably intended for would-be attackers, that proclaimed “We are unarmed.”

WE ARE UNARMED

Inside we found an orderly, stable, clean mini-city digging in for the long haul. A main road of sorts was lined with the flags of nearly every Native American nation, smoke rose from a couple of well-supplied kitchens, and winter clothes were being distributed from several depots. Shelters ranged from the tiny one-person variety to huge army tents and dozens of tipis.

Main Street Oceti Sakowin

In a central square a sacred fire burned continuously. On one side of the square a steady stream of announcements emanated from an open-air administrative booth.

Off to the south was a small stable for the beautiful horses later ridden bareback by a protectors’ cavalry of sorts and, on a hill, a variety of “offices” housed a media team, the Indigenous Environmental Network, and a legal aid/medical team of doctors and lawyers. It was at that latter tent that the seriousness of the endeavor hit home. Briefed on what to expect and how to behave if arrested, we filled out forms with our next of kin contacts and special needs and were urged to write the legal aid phone number on our arms. I was somewhat amused, when, having later remembered my need for my asthma inhaler, I returned to note that on the form I had filled out earlier. Rifling through a stack of forms, a member of the staff found mine, now bearing a stencil pen star and a circle around the “transgender” I had included under “special concerns.”

Taking care of legal affairs

For three days, we spent time walking around the camp, meeting the campers, and listening… above all listening…listening to the stories, the history of indignities, the yearning for justice. I again recalled those Lakota words of wisdom “Listen to the wind, it speaks. Listen to the silence, it talks. Listen to the heart, it knows.” It was clear that what was about water had evolved into something even bigger. It was no longer just about a pipeline.

That was a theme that we heard later that evening during non-violence training in the gym of the Cannon Ball school, as one tribal leader after another described the richness of their culture and how they had been denied access to it.

At that meeting, John Floberg, who had earlier been handed a check for $2,000 from All Souls, Berkeley, stressed again and again that our witness the next day was to be peaceful, prayerful, and legal. It was, therefore, saddening to see a rump group of Presbyterians take the microphone under false pretenses and urge provocative actions that would surely lead to arrests and most likely violence.

John preaches non-violence

Despite that effort, our action the next day, November 3, unfolded peacefully and indeed prayerfully. For some of us it began with a 7:30 am sunrise Eucharist at Rev. Floberg’s St. James Church. North Dakota Bishop Michael Smith presided and Deacon Brandon Mauai, a member of the Standing Rock tribe, delivered a moving sermon about how he had been denied his heritage, how he would ensure that his children would not, and how he would forgive.

After a breakfast on the run – a banana in my pocket and a bagel smothered in peanut butter – we drove in caravan to the camp. I’ll never forget the shouted “Thank You”s from the campers assembled on the hill. Gathering at the sacred fire under the rising sun, leaders of our different faith traditions read our renunciations of the Doctrine of Discovery. Elders from the several tribal nations then burned a copy of the hated document in an abalone shell.

Renouncing the Doctrine of Discovery And burning it.

In our hundreds, we were individually blessed by those elders with the smoke of burning sage, as we marched in silence to the bridge. For a stretch, I also felt blessed, helping Warren Wong, a lay General Convention deputy, carry the huge Episcopal flag that has flown so many years from San Francisco’s St. James Church where I once served as deacon.

We were sent off with a blessing

At the bridge, beyond which close to forty police cars and a few armored vehicles stood ready to repel the faithful, while, overhead, a police helicopter circled low in an apparent effort to drown out our prayers and songs. Perhaps they felt threatened by the rousing rendition of “God’s Gonna Trouble the Waters” by the Rev. Stephanie Spellers, Canon to the Presiding Bishop.

As the prayers turned to speeches, I drifted to the fringes, anxious to talk with others in the crowd – a Muslim couple, a rabbi, a developmentally disabled deacon, Native Americans from Standing Rock and as far away as Mexico and the Peruvian Amazon, the young warriors on horseback and guarding the bridge, lest the previous night’s troublemakers seek to spark a confrontation.

There were Muslims, Jews, Christians and warriors on their horses.

And, at the end, we formed a huge Niobrara Circle of Life, each of us walking the circle, passing the peace. How incredibly moving to look into each other’s eyes, to shake each other’s hand, as we offered our “Peace,” a greeting I interspersed with “Shalom,” “Salaam,” “Paz del Senor, and the occasional African greeting “I see you.” Having removed my sun glasses to do just that, I left myself vulnerable. They could see my tears. But, then, too, I could see theirs.

The Niobrara Circle

Returning to the bridge long enough to enjoy a sandwich, we dispersed as silently and peacefully as we came, to return to our homes and tell our stories…as I have tried to do here.

To be sure, I and my sister deacons returned to the camp after lunch and again the next morning to continue the conversations we had started the day before. And, on Friday morning, we discovered that the “law enforcers” had strung rings of barbed water across the bridge and into the water on either side. And I found myself asking “Are we still in America?”

The ugliness of it all

Repelled by the ugliness of it all, we climbed into our rental car and drove down to Fort Yates, a pretty town that is home to the tribal headquarters and Sitting Bull College where we enjoyed a particularly rewarding conversation with the school’s Library Director Mark Holman.

Recalling the history I had learned at Wounded Knee and how the events leading up to the massacre there had included the killing of Sitting Bull at Fort Yates, I left a tiny stone on his grave.

I had, I thought, completed my witness But, returning to Prairie Knights Casino and taking the elevator up to my room, I found myself sharing the elevator with a Native American mother and her adult daughters. “Were you part of the action by the faith leaders?” she asked. When I answered “Yes,” she threw her arms around me and hugged me ever so tightly…no words, just a firm hug. And, when I got off, a smile and simple “Thank you.” I slept well.

Now I’m home, still learning, working my way through Mark’s recommendation, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, the history we non-Native Americans have yet to learn…the history so well summed up by the words of Tatanka-Iyotanka (Sitting Bull) engraved on his memorial:

What treaty that the whites have kept has the red man broken? Not one. What treaty that the whites ever made with us red men have they kept? Not one. When I was a boy the Sioux owned the world. The sun rose and set in their lands. They sent 10,000 horsemen to battle. Where are the warriors to-day? Who slew them? Where are our lands? Who owns them? What law have I broken? Is it wrong for me to love my own? Is it wicked in me because my skin is red; because I am a Sioux; because I was born where my fathers lived; because I would die for my people and my country?

Yes, it’s more than just a pipeline.

But the struggle to block the pipeline goes on at Oceti Sakowin. Winter has arrived. A foot of snow has fallen and, as I write this, the high was 38 with wind whipped white out conditions across the plains. Worse yet, a defiant Kelcy Warren, the CEO Energy Transfer Partners, insists that "There's not another way. We're building at that location,” adding that the Army Corps of Engineers should cease its “political interference” and get out of the way. Perhaps bolstered by the President-Elect’s investment in the pipeline and disbelief in climate change, North Dakota Governor Jack Dalrymple has labeled the Corps-ordered delay “unnecessary and problematic.”

It is clear that further actions to stand with the people of Standing Rock, both at Oceti Sakowin and in local non-violent demonstrations (such as one I participated in Albany, California) will be necessary to demonstrate solidarity with our beleaguered Native American sisters and brothers and to raise public awareness about an issue that has gone unreported in the corporate media.

To that end the East Bay chapter of the Episcopal Peace Fellowship is planning to host an early January forum to share the experiences of those who have been to Standing Rock and to provide information to others who may wish to go or otherwise support the people of Standing Rock. Those in the area interested in sharing their experiences or interested in learning more at such a forum should contact Vicki Gray at vgray54951@aol.com or (707) 554-0672.